Day 46 - Grazing wheat & OSR

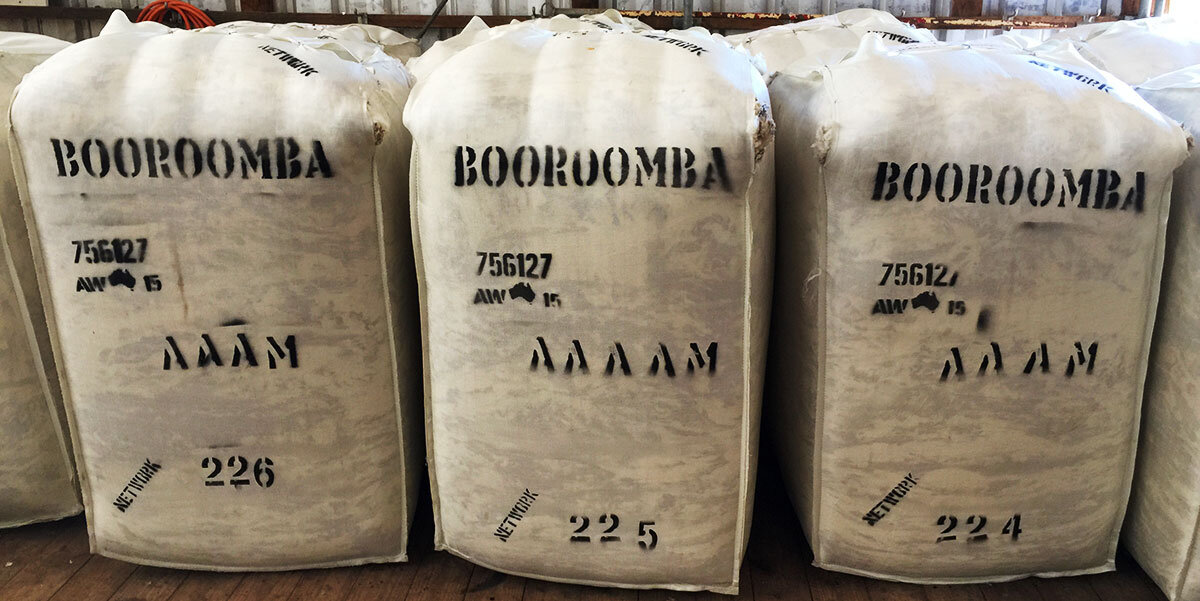

In March we came to Canberra for a few days with all the 2014 scholars from around the world for a conference, and today was a bit of a flashback. Not only did I accidentally stay in the same hotel, but I also visited a sheep farmer call John Hyles, just as we had back then. John farms 5000ha at Booroomba, just south of Canberra, and has a small flock of Merino sheep (currently 18,000), and also 1,000 Angus cattle. Because this must not keep him busy enough, he also runs a quarry business selling sand, gravel, river pebbles, top soil and land fill. He's also interested in property development, and arable farming. Many pies to be fingered. At the moment they are shearing, at a rate of about 1,700 animals per day. It's an impressive setup. I'll use a few photos to decorate this post, which is really about who I saw before I drove out to John's.CSIRO is Australia's national research organisation, and it does a lot of work with agriculture. Hugh Dove is a scientist who has spent 15 years looking in to the grazing of wheat and OSR (Oilseed Rape, or Canola as they call it here). This is of particular interest to me, as we have a wheat grazing trial at home this year. Grazing OSR is something I have thought about a little bit, especially as I reckon it may be a tool to use in our fight against the flea beetle. Having spoken with Hugh for a couple of hours, the principals are largely similar between the two crops.Firstly, it is important to get the plant sown as soon as possible. They have actually done trials (and some farmers use the technique for real) where OSR is planted so early, and then grazed multiple times, that by harvest is has been in the ground for 15 months. That's pretty extreme, and apparently it can allow root diseases to become problematic. There are other potential problems with very early drilling, such as aphids that cause BYDV (Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus), and fungal diseases. But if these can be avoided, earlier drilling means more biomass to be grazed. It should also mean better root growth, which could potentially be useful later in the season.

In March we came to Canberra for a few days with all the 2014 scholars from around the world for a conference, and today was a bit of a flashback. Not only did I accidentally stay in the same hotel, but I also visited a sheep farmer call John Hyles, just as we had back then. John farms 5000ha at Booroomba, just south of Canberra, and has a small flock of Merino sheep (currently 18,000), and also 1,000 Angus cattle. Because this must not keep him busy enough, he also runs a quarry business selling sand, gravel, river pebbles, top soil and land fill. He's also interested in property development, and arable farming. Many pies to be fingered. At the moment they are shearing, at a rate of about 1,700 animals per day. It's an impressive setup. I'll use a few photos to decorate this post, which is really about who I saw before I drove out to John's.CSIRO is Australia's national research organisation, and it does a lot of work with agriculture. Hugh Dove is a scientist who has spent 15 years looking in to the grazing of wheat and OSR (Oilseed Rape, or Canola as they call it here). This is of particular interest to me, as we have a wheat grazing trial at home this year. Grazing OSR is something I have thought about a little bit, especially as I reckon it may be a tool to use in our fight against the flea beetle. Having spoken with Hugh for a couple of hours, the principals are largely similar between the two crops.Firstly, it is important to get the plant sown as soon as possible. They have actually done trials (and some farmers use the technique for real) where OSR is planted so early, and then grazed multiple times, that by harvest is has been in the ground for 15 months. That's pretty extreme, and apparently it can allow root diseases to become problematic. There are other potential problems with very early drilling, such as aphids that cause BYDV (Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus), and fungal diseases. But if these can be avoided, earlier drilling means more biomass to be grazed. It should also mean better root growth, which could potentially be useful later in the season. The second rule is that it is not so important when the grazing starts, but timing when to remove the animals is critical. At the very latest they must be gone by the time stem extension starts, which in the UK on wheat is probably the end of March. However, the more time the plant is given to recover the more chance it has of not losing any yield potential. Amazingly, it is possible to graze almost all of the leaf area off and still not affect yield; they have measured increased photosynthetic activity to compensate for this loss of leaf area.One of the big benefits of this system is in weed control. Particularly when grass weeds like ryegrass are a problem, they are finding that the sheep will eat it all up, and the grazed areas are cleaner than the un-grazed. The ultimate selective herbicide! Apparently the effect is so pronounced that for some farmers it is the main reason they are grazing the crops.The next point needs a little bit of a science lesson, which I will try not to get wrong. Back in the day, when wheat was first being bred into what we use today, the strain that became bread-making wheat (as opposed to noodle-making, or Durum) picked up a gene called Kna1. Without going in to details (because I don't know them and the internet here is too slow to look it up), this gene means that the plant uses potassium (K) instead of sodium (Na). This is a useful adaptation to have, because it gives a greater ability to grow in saline soils; however it also means that there is almost no sodium at all in the leaves. This only becomes a problem when wheat is fed to ruminants, because they require a certain level of sodium to allow the uptake of magnesium. So, if they don't get enough sodium, they will develop hypomagnesemia, or grass staggers as we call it. The solution is to supplement the animals with a mix of salt and magnesium oxide. This will increase growth rates by around 40%, for very little cost. No brainer.Interestingly, when grazing oats, which do not have the Kna1 gene, there is no response to supplementing, and when grazing OSR, it is actually detrimental - for as yet unknown reasons.

The second rule is that it is not so important when the grazing starts, but timing when to remove the animals is critical. At the very latest they must be gone by the time stem extension starts, which in the UK on wheat is probably the end of March. However, the more time the plant is given to recover the more chance it has of not losing any yield potential. Amazingly, it is possible to graze almost all of the leaf area off and still not affect yield; they have measured increased photosynthetic activity to compensate for this loss of leaf area.One of the big benefits of this system is in weed control. Particularly when grass weeds like ryegrass are a problem, they are finding that the sheep will eat it all up, and the grazed areas are cleaner than the un-grazed. The ultimate selective herbicide! Apparently the effect is so pronounced that for some farmers it is the main reason they are grazing the crops.The next point needs a little bit of a science lesson, which I will try not to get wrong. Back in the day, when wheat was first being bred into what we use today, the strain that became bread-making wheat (as opposed to noodle-making, or Durum) picked up a gene called Kna1. Without going in to details (because I don't know them and the internet here is too slow to look it up), this gene means that the plant uses potassium (K) instead of sodium (Na). This is a useful adaptation to have, because it gives a greater ability to grow in saline soils; however it also means that there is almost no sodium at all in the leaves. This only becomes a problem when wheat is fed to ruminants, because they require a certain level of sodium to allow the uptake of magnesium. So, if they don't get enough sodium, they will develop hypomagnesemia, or grass staggers as we call it. The solution is to supplement the animals with a mix of salt and magnesium oxide. This will increase growth rates by around 40%, for very little cost. No brainer.Interestingly, when grazing oats, which do not have the Kna1 gene, there is no response to supplementing, and when grazing OSR, it is actually detrimental - for as yet unknown reasons. And what about yield? CSIRO work has show all possibilities, from increases to decreases. Overall their results have shown a negative impact, of -8%, but with a very large standard deviation (25%). So basically they are not quite sure. The whole idea will live or die on this point, it will not be economical with any significant reduction.I think it's a really exciting prospect, which could potentially open up a new system of farming. Integrating cover crops, OSR and wheat grazing effectively could provide effectively free forage for 4-6 months of the year. [That's free to us, not to the grazier, in case our sheep man is reading this] Tie in companion cropping, and the selective four-legged herbicide, and it looks even better.One last thing: I finally found a good place to use the slo mo video that my phone does. I think this is quite fun.[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vkmMC31y-r4[/embed]

And what about yield? CSIRO work has show all possibilities, from increases to decreases. Overall their results have shown a negative impact, of -8%, but with a very large standard deviation (25%). So basically they are not quite sure. The whole idea will live or die on this point, it will not be economical with any significant reduction.I think it's a really exciting prospect, which could potentially open up a new system of farming. Integrating cover crops, OSR and wheat grazing effectively could provide effectively free forage for 4-6 months of the year. [That's free to us, not to the grazier, in case our sheep man is reading this] Tie in companion cropping, and the selective four-legged herbicide, and it looks even better.One last thing: I finally found a good place to use the slo mo video that my phone does. I think this is quite fun.[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vkmMC31y-r4[/embed]